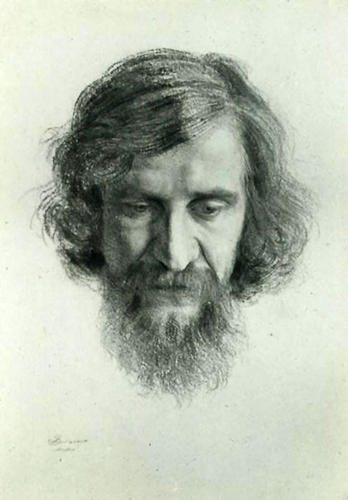

In 1972, after Vietnam, Long traveled to Florence, Italy and apprenticed himself to Pietro Annigoni, one of the few classic realist painters of the 20th century.

"The Last Living Italian Master of the 20th Century"

Self Portrait; Pietro Annigoni

For 9 years Long worked beside Annigoni and learned the art of True Fresco. After completing several frescos in Italy, including the Abbey de Montecassino, Long brought his fresco talent to America.

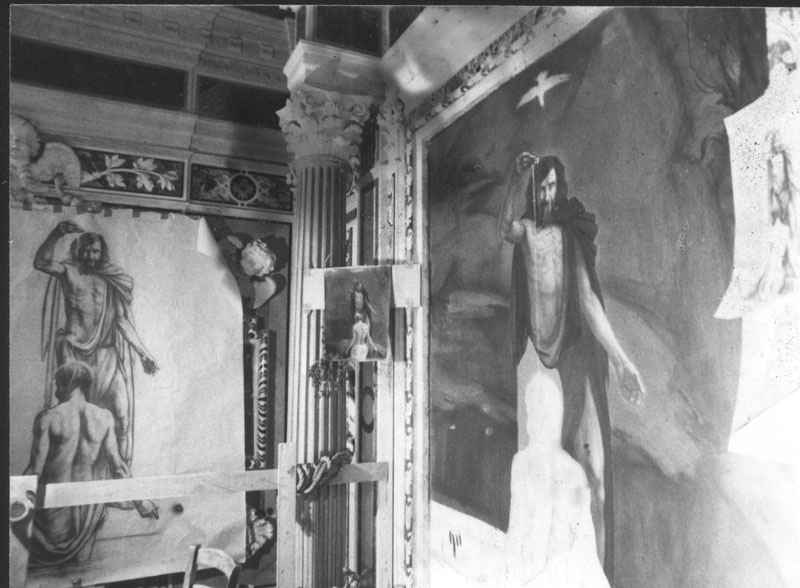

(Below is a Collection of studies done for the Fresco in the Abbey De Monte Cassino)

Since 1978 Long has completed over 30 frescos in the United States.

Buon Fresco (True Fresco)

Fresco is the medium Michelangelo chose when he painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The technique involves mixing sand and lime, placing the mix on the wall and paintings it while it is still wet. Fresco paintings is a tenuous art. So quickly does the bonding of the pigment to wet plaster take place that great skill and meticulous planning must be maintained in order to achieve the beautiful result.

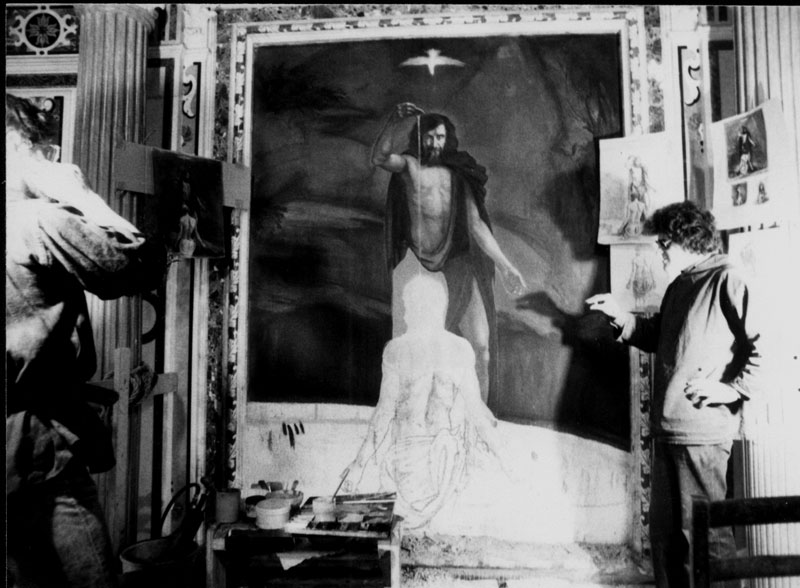

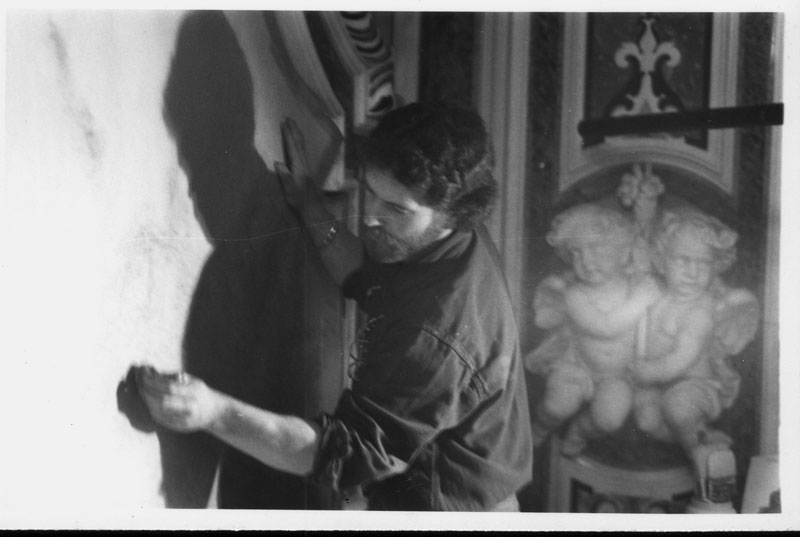

B.F.Long IV working of the Fresco at St. Peters (Charlotte, NC)

The Fresco Process

Fresco; From the Italian word for "Fresh"- refers to the process of paintings on plaster and the resulting product. The fresco process is a long and tedious one involving the application of three layers. First, a base coat of plaster - lime mixed with sand and water - is applied to the wall.

One a second, finer coat of plaster -The Arricio- a red outline called the Senopia is transferred from the studio drawings.

The Final Layer is the Intonaco -one part line and one part sand - to which hand-ground pigments suspended in water are applied.

The artist must apply the pigments before the plaster dries, thus the fresco must be painted in sections called Giornata, Italian for "the work that can be done in a day".

Sometimes the lines between the sections, called "day marks", are visible. As the plaster dries, a chemical reaction takes place and crystals of calcium carbonate form, locking the molecules of the pigment in place. The lime in the plaster provides each fresco with a built-in source of illumination, lending a subtle glow to the work of art.

This technique found new life during the Italian Renaissance, when some of the most famous works were created, including Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper in Milan and Michelangelo's ceiling in the Sistine Chapel.

B.F.LongIV working on the Fresco in Community Center of Morganton, NC